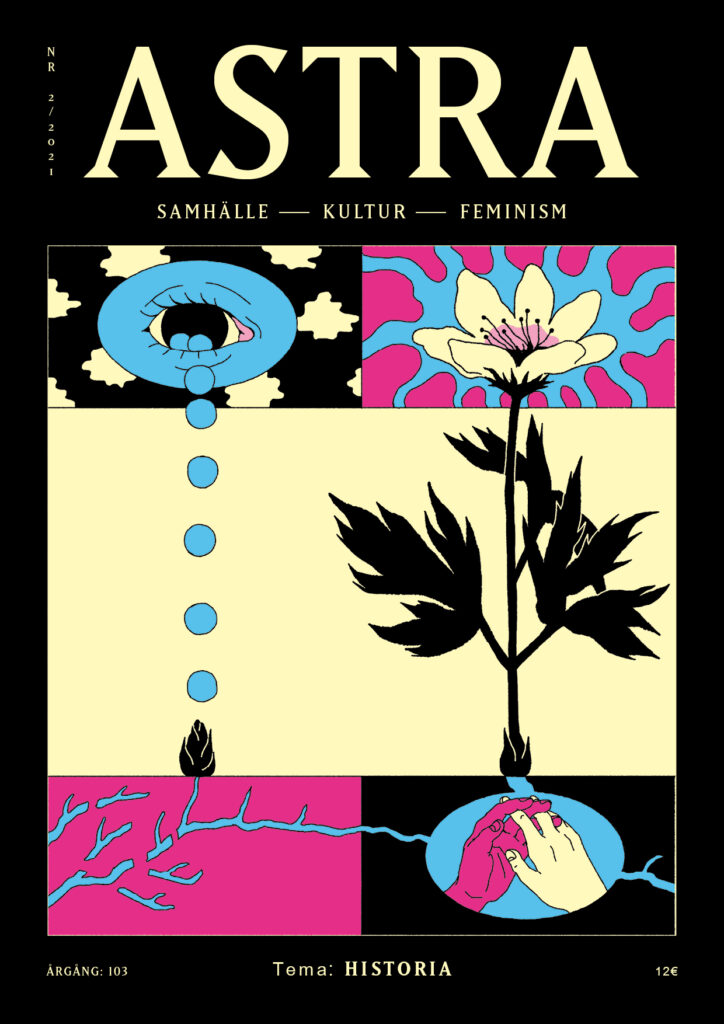

2/2021: Historia

Astra 2/2021

Tema: Historia

Astra nummer 2/2021 har temat Historia och innehåller personliga berättelser om rötter, generationstrauman, att leta föregångare och att kräva tillbaka sitt arv.

Vi möter bland annat gästredaktören från förra numret, Jasmine Kelekay, i en kolumn om den afrosvenska kampen för ett erkännande av nionde oktober som nationell minnesdag för slaveriets avskaffande i Sverige. Kerstin Andersson, en av trettiotalet samer som driver frågan om att återbörda stulna samiska offergåvor till Sápmi, har skrivit en artikel om den skändade offerplatsen Unna Saiva. Vi får även ta del av konsthistorikern Yilin Mas personliga och poetiska text om att tillhöra den kinesiska diasporan i Finland och doktoranden Marika Kivinens artikel om att minnas kolonialism och undersöka hur rashygien bedrivits i Finlands "svenskbygder".

Numrett kan får gratis mot porto om du mejlar [email protected], samt läsas digitalt här:

Medverkande

Samar Zureik

Mats Wickström

Sunná Valkeapää

Iona Roisin

Nina Nyman

Yilin Ma

Linnea Lundborg

Marika Kivinen

Minjee Hwang Kim

Jasmine Kelekay

Dionysia Kang

Jet Hilferink (endast i papperstidningen)

Emma Göransson

Nina Grönlund

Rosanna Fellman

My Danvind

Shia Conlon

Maria Bodin

Fatuma Awil

Kerstin Andersson

Läs Astra digitalt här (PDF)

Live 13.4: Svart feminism och kultur i Norden – Vem får synas och höras och på vilka villkor?

[English below]

Livestreamat samtal över Facebook kl. 18.00, tisdag 13.4.2021.

Språk: Engelska

Under sommaren 2020 mobiliserade sig svarta aktivister i Norden och anordnade Black Lives Matter-demonstrationer för att visa solidaritet med svarta amerikaner samt markera att statligt våld och strukturell rasism även drabbar svarta människor i Norden. Sedan dess har anti-svart rasism än en gång lyfts fram i både kultur- och samhällsdebatten.

Mycket av detta arbete och engagemang har utförts av svarta kvinnor, en grupp som länge har organiserat sig kring rasism, sexism, och andra former av förtryck i Norden. Samtidigt osynliggörs och marginaliseras ofta svarta kvinnors historier, upplevelser och perspektiv, även inom antirasistiska, icke-vita och feministiska rum.

Denna paneldiskussion kommer därför att centrera fyra svarta kvinnor från olika nordiska länder som genom sitt kulturella, intellektuella och politiska engagemang har bidragit till att lyfta fram representationer av svarta kvinnor och deras upplevelser och perspektiv. Samtalet modereras av Jasmine Kelekay.

Evenemanget arrangeras i samarbete med Nordisk kulturkontakt.

Jasmine Kelekay är en afrofinlandssvensk forskare och aktivist med fokus på anti-svart rasism och svart aktivism i Norden. Hon doktorerar i sociologi vid University of California, Santa Barbara och är gästdoktorand vid Centrum för Mångvetenskaplig Forskning om Rasism (CEMFOR) vid Uppsala Universitet. Kelekay är gästredaktör för tidskriften Astras nyutkomna temanummer om svart feminism i Norden.

Deltagare i paneldiskussionen:

Judith Kiros är en svensk poet, litteraturvetare, kritiker och journalist.

Kiros är en av grundarna till den antirasistiska och feministiska plattformen Rummet, som grundades 2013. År 2019 var hon delaktig i att skapa Kontext Press, en tvärmedial plattform för eftertänksam journalistik och kritisk underhållning. Kiros debuterade 2019 med den kritikerhyllade diktboken, O, som behandlar bl.a. svarthet och kön.

Monica Gathuo är en finländsk mediaproducent och aktivist baserad i Helsingfors, Finland. Gathuo är samordnare för ARMA Alliance (Anti-Racism Mediam Activist Alliance) och hon forskar kring hur rasifierade kvinnor i Finland använder sig av digitala medier. Hon samarbetar med POC-ledda organisationer och initiativ ledda av rasifierade ungdomar.

Phyllis Akinyi är en dansk-kenyansk dansare, koreograf, performancekonstnär och dansforskare. Akinyi arbetar med samtida folklore, det som är ‘varken det ena eller det andra’, och spirituella riter i diasporan. För tillfället är hon i NYC för att utveckla hennes senaste uppsättning kring temat sorg som får premiär i maj 2021. Hon är ordförande för De Frie Koreografer och arbetar passionerat för att det skandinaviska konstfältet ska utvecklas, expanderas och bli mera inkluderande av BIPoC konstnärer och icke-västerländska kulturer.

Deise Faria Nunes är en brasiliansk performancekonstnär och konstforskare baserad i Norge. Nunes är doktorand vid universitetet i Agder och forskar inom programmet Theater in Context. Hon är grundare för bolaget Golden Mirror Arts Norway som fokuserar på konstnärliga produktioner av svarta kvinnors och dess distribution. Nunes är även verksam som frilansskribent.

***

Black Feminism and Culture in the Nordics: Who gets to be heard

Live stream discussion on Facebook 6pm Finnish time, Tuesday 13th of April 2021

Jasmine Kelekay is an Afro-Finland-Swedish researcher and activist focusing on anti-Black racism and Black activism in the Nordics. She is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara and a visiting researcher at the Centre for Multidisciplinary Studies on Racism (CEMFOR) at Uppsala University. Kelekay is guest editor for Astra’s recently published special issue on Black feminism in the Nordics.

Delta i nästa nummer av Astra – Tema Tro

Astra tar nu emot texter till nummer 3/2021 på temat "Tro"!

Temat kan tolkas fritt: Kanske för det tankarna direkt till gudstro, religion eller annan andlighet, kanske till någon helt annan form av tro. Tro på ett politiskt system? Tro på feminismen?

Tro i religiös eller andlig bemärkelse är ett ofta omdiskuterat ämne inom feminismen. Att abortmotstånd, homofobi och konservativa uppfattningar om genus och könsroller ofta sägs ha religiösa motiv är ingen nyhet. Samtidigt vore det långt ifrån sant att påstå att feminismen som rörelse inte har egna kopplingar till olika former av tro och andlighet. Astras svenska syskontidskrift Bang hade till exempel en egen horoskopsida i varje nummer under en period – självklart kopplat till astrologi, något vi ofta hör människor säga att de antingen "tror" eller "inte tror" på.

Den feministiska kampen kan dessutom kopplas ihop med tro genom olika dekoloniala rörelser och ursprungsbefolkningars kamper.

Många feminister lägger tarot, mediterar, utför olika former av ritualer och intresserar sig för magi. Och självklart finns det feminister inom alla religioner. Kanske hör du till dem? Eller sällar du dig till dem som forskat kring skärningspunkten feminism/tro? Vi är i vanlig ordning mycket nyfikna och spända på att få läsa era bidrag!

Hur? Skicka ditt utkast eller din idé till text (essä, kritik, artikel, intervju, reportage, poesi, novell, you name it) till [email protected]. Bidrag med utförliga idébeskrivningar och bifogade textutkast uppskattas och har större chans att komma med i tidskriften!

När? Skicka din idé senast fredagen den 23 april. Deadline för färdiga bidrag kommer att vara den 14 maj.

Vad? Temat för Astra 3/2021 är alltså Tro, och du är välkommen att komma med din egen vinkling. Vi välkomnar bidrag som går i linje med en intersektionell, antirasistisk, klimataktivistisk och transinkluderande feminism. Redaktionen läser svenska och engelska, men är publicerar även texter på andra språk, såväl som flerspråkiga bidrag.

***

In English:

Astra are looking for contributions for vol. 3/2021, which will be on Belief!

This theme can be widely interpreted: Maybe you're immediately thinking of religion, belief in God or other forms of spirituality. Or maybe your associations go to belief in a political system, or in feminism?

Belief in the religious or spiritual sense has many connections to the feminist movement. Both to the struggles feminists face, such as the anti-abortionist movement, homophobia and conservative views on gender, which are all often said to have religious motifs. But also to the ways spirituality is present within the feminist movement itself. Many feminists engage in practices such as astrology, tarot, rituals and magic. And of course feminists are present within all religions. The feminist struggle is also connected to belief and spirituality through decolonial movements and struggles for indigenous rights.

Maybe you're one of those engaging both in spirituality and feminism, or maybe you've conducted research on the topic? We are, as always, really looking forward to read your contributions!

How? Send your abstract/draft/idea (we’re welcoming texts of all genres) to [email protected]. We appreciate a submission with an extensive description and attached draft of your text (submissions with drafts attached have a higher chance of being published).

When? Send us your ideas and drafts by Friday the 23th of April. Deadline for finished texts will be the 14th of May.

We read Swedish and English, but are open for publishing texts also in other languages, as well as multilingual pieces.

Aino-kunto – Av Mwenza Blell

The sound of Finnish women speaking to each other in Finnish is lovely and you want to weep when they speak to each other in English, which is such a different sound, full of pauses and the charm of Finnglish phrasing, because they are so kind to make the effort for you, who have no other language. You wish you had a language like they do but your ancestors had their language taken from them, you wonder if the Finnish women think about your stolen language. You are together in the beautiful surroundings of the Ateneum café. After the quiet solitude of walking around the museum, you are relieved now to be with others, even though you don’t know them very well. They are talking to each other about exercise. One of them, a woman you’ve met only once, invites you to a boxing class and you are so grateful for a friendly invitation that you say yes.

"You can hear Finnish people arguing with you in your head, arguing with your every thought about Finland, what does that mean?"

The gym where the boxing class happens is new. Everything seems to be new in Finland. Maybe new is not the right word, maybe it should be well-cared-for? You can hear Finnish people arguing with you in your head, arguing with your every thought about Finland, what does that mean? The gym is deep below the city, it is very clean and bright, you notice that you are not allowed to use the lift if you are going to the gym, and as you realise there is another flight of stairs below this one and then another below that one and still yet another, you start to plan for what you will say to get them to let you use the lift instead of climbing the stairs on your way out, can you say you have a disability or injury? Would you be able to pull that off? Then you feel shame wash over you, of course, of course, the gym should not let people use the lift, because… ehrm, something about healthy activity and modern conveniences, you can’t remember initially but then you can hear people in your head confidently explaining the obvious wisdom of expending more energy doing everything so you can lose weight and stay fit but you know you often don’t have the energy to carry all that self-blame AND to do everything the hard way.

Blonde women whose hair is in ponytails, whose narrow bodies are held but not strangled by colourful sportswear, are walking around. You can see how your own clothes, which you knew would stand out a bit, are more different than you’d thought. Everyone in Helsinki wears black but not in the gym you now realise, only on the streets. The other people are wearing the new generation of shiny synthetic sportswear, not just old (and slightly sagging) jersey blend leggings and two faded hand-me-down camisoles over a regular bra (you realise that you forgot sportsbras even exist). These are the closest things you own to sportswear and you thought about what to wear for weeks, hoping not to look so out of place that people would feel embarrassed for you. You realise the embarrassing thing is that you are poor and it doesn’t help being fat, either. You notice that indeed every person is wearing this very up-to-date sportswear and you wonder if it even comes in your size and imagine the pain of struggling into the shiny leggings (which seem not to be very stretchy somehow!?).

"You can see how your own clothes, which you knew would stand out a bit, are more different than you’d thought. Everyone in Helsinki wears black but not in the gym you now realise, only on the streets."

You go through the big door with the cut-out of a person in a dress painted on it: the women’s locker room. You don’t even have shoes to wear to work out, you put your heavy all-weather work shoes in the locker. You don’t own suitable shoes and hope you will be able to get away with being barefoot for the class. Nobody else is barefoot. All the other women are putting on socks and those lightweight specialist exercising trainers which you have never owned but have noticed people wearing. Then you realise you forgot both your towel and deodorant and want to cry because you are already sweating, hot, stinging sweat from anxiety, so you will definitely need both. You tell the one person you know who is next to you in the locker room and you are amazed when she says, ‘you can share mine’, does she not think you are disgusting? It is an impossible kindness. It hadn’t occurred to you that people might not have some feeling that because you are weird and black and fat that your body is dangerous and possibly infectious. You are sure this is how people have treated you in the past. You try not to show how much this gesture of acceptance affects you.

In Finland people take padlocks around with them in case they use lockers. You did not know this, of course, but you are keen to become like them and carry a padlock as soon as you can figure out where to buy a padlock in this strange city. Your towel-sharing friend lets you borrow a lock. You feel inadequate but grateful to be cared for. Is this what Finland wants from you?

Just when you feel you’ve gotten on top of your emotions in the locker room, it is time to leave and go into the actual space where the class is going to take place. Dread is playing loudly in your ear, you are holding an old plastic bottle of something you found in the fridge at home which looks like water but you worry that it’s not and you worry that it’s old and full of germs that might make you feel unwell so you resolve not to drink it in the class but just to use it as a prop since everyone else has some kind of bottle with them. You looked for nice-looking reusable water bottles in shops, but they cost more than 20 euros which made you sad and frustrated. Helsinki has made you poorer. Why should being poor mean you have to choose between thirst, the indignity of carrying an old jar to meetings with rich people, or risking harmful toxins leaching from plastic bottles you reuse?

"You looked for nice-looking reusable water bottles in shops, but they cost more than 20 euros which made you sad and frustrated. Helsinki has made you poorer. Why should being poor mean you have to choose between thirst, the indignity of carrying an old jar to meetings with rich people, or risking harmful toxins leaching from plastic bottles you reuse?"

The coach comes over to say hello, she is one of the narrowest blonde women you’ve seen today but she smiles at you and tries to speak English when she realises you don’t understand Finnish and she is older than you and you trust her because of this. She tells you that you need to take your rings off and you thank her and agree that, of course, you need to do this. The first ring comes off easily but the rest do not and you begin to panic because the class is going to start and your fingers are hurting and turning purple in turn as you try to get the rings off. People can see you do this. It’s terrible. All these rings you wear because you love the people who gave them to you and you are far away from them and now they are embarrassing you. You tell the coach you will try to use soap to help get them off and run out of the room just to escape people seeing you struggle. Is it too late to escape? At what point would you give up if it doesn’t work? Some tears are collecting in your eyes and you feel very hot as you run cold water over your hands to shrink your fingers. You are so grateful when the soap eventually works and you run back into the room and drop your rings on the floor by your bottle.

"You get a better look at everyone and they are all very variable in height and age but all much thinner than you, all of them are white."

The class has started with a warm-up which you’ve mercifully missed the beginning of because of your rings, you realise you had forgotten about warm-ups and that this is often the most painful part of organised sports for you because the coach doesn’t realise that so much running is beyond your capacity, much less being a mere warm up for the activity to come. You wonder how long you will last. The room has mirrors on each wall, you carefully avoid looking at yourself, you are all running in a circle and you hope people will not be so unnecessarily athletic as to pass you in the warm up but some do. You get a better look at everyone and they are all very variable in height and age but all much thinner than you, all of them are white. You make a blindspot in your vision for yourself in this mirrored room, so you don’t have to see yourself. You only catch uncomfortable glimpses of yourself from time to time. Glimpsing yourself accidentally reminds you how different you look to other people in every way. You wonder if thin white people ever forget how thin and white they are when surrounded by more robust and brown people. Is it a sign of a lingering wish to be white and thin that you forget? It’s a very sad thought which is appropriate for how much you are slowing down, you wonder how long she will have you run. She makes you run sideways and you are relieved even though this makes you stumble more and slow down further because you are beyond worrying about embarrassing yourself now, you are just hoping to get through the experience.

Finally, the running is over, and you have to remember not to drink from your bottle while waiting for the next activity.

You and all the other women are instructed to take a pair of boxing gloves for yourselves from the shelves. You don’t know your size but the woman who offered her towel suggests her size might be the same as yours. The gloves fit fine. Nothing is wrong with your hands. Your hands are standard.

The coach does not seem to expect you to fail at learning to box, she seems to think you are strong and capable. You remember all the coaches who you knew believed you were incapable. You realise that you might be built a bit like your brother, why did you never think of that before? You are strong. The coach can see it. You have not trained to be strong but then you have also not deliberately starved yourself in years.

"Glimpsing yourself accidentally reminds you how different you look to other people in every way. You wonder if thin white people ever forget how thin and white they are when surrounded by more robust and brown people."

There are many movements the coach shows you which you can’t copy perfectly but people are not looking at you because they are busy trying to do things themselves and you are so relieved you begin to cool down. You survive all the activities, you do not cry, people carefully show you what to do, especially the coach.

Then it is over and you go back into the locker room.

Their bodies. You glance from one to the next whilst trying not to move your head or act at all unnaturally so as not to give anything away, they seem so relaxed, like they do this every day. Like it is the women’s sauna at home with their sisters and aunties. Looking at them you can see that somehow they are all lovely and you can see that they are infinitely closer to what bodies should be than anything you’ve ever seen looking down or in a mirror since you learned how to look. Growing up is learning how to look, it is a path burned in your brain so you know just what bodies should look like. What must it be like to feel so unburdened by your own wrongness? You have to take off your clothes so you do and feel like your every move is too awkward to blend in.

The shower room is off to the side of the women’s locker room. You peek inside when someone opens the frosted glass door to go in. It is one big room with no dividers, just metal pipes and shower heads and knobs to turn off and on and white tile. You didn’t anticipate there even being a need to shower, you can’t remember ever needing to shower before in a communal situation. Even during that short period when you went to the gym as a student, then you never even learned where the showers were.

"This is a beautiful scene, you know about these beautiful scenes, you know what they look like, this is a painting of beautiful white women, of course, bathing beauties actually because you don’t have to say white when you say bathing beauties or even beauties, especially in art, and there is never anything like you in them."

You enter the room holding the small towel you have been lent loosely around you. The shower room is full of steam and you realise that steam and soap suds are also both white, of course. Just like when someone describes a gym as pristine and you imagine a white space. There is something so powerful about the women showering, soap suds and water sliding off their smooth bodies, steam in the air. Their bodies are powerful, the scene is powerful, you feel in the core of you that you are out of place. This is a beautiful scene, you know about these beautiful scenes, you know what they look like, this is a painting of beautiful white women, of course, bathing beauties actually because you don’t have to say white when you say bathing beauties or even beauties, especially in art, and there is never anything like you in them. You are out of place, really, you are. You are happy to leave the beautiful scene to be as it is because you appreciate such things, you know how to see beauty, so you cast a glance into the corner of the room. Where is the edge of this painting?

"Between the reality you are in and the world beyond, there is a margin, you edge toward it and wonder if only you can see it and imagine that must be the case."

Between the reality you are in and the world beyond, there is a margin, you edge toward it and wonder if only you can see it and imagine that must be the case. You try to look casual and slide your toe and then your foot over the margin. You are afraid of being noticed and mentally beg the women not to turn around and notice you. It is a big painting and you are very small. As you slide your leg out, you feel with your foot along the wooden frame, you are relieved as your foot finds the flat side of a golden swastika and you can lower yourself down, one leg at a time, and then drop away.

The writer is an anthropologist. She is a research fellow at Newcastle University, UK. In 2019, she carried out fieldwork in Finland.

This short story is thematically linked to Mwenza's article "On the Cultivation of Black Feminist Pattern Recognition", which was published in Astra 1/2021 on Black Feminism in the Nordics.

On the Cultivation of Black Feminist Pattern Recognition – av Mwenza Blell

"You can hear Finnish people arguing with you in your head, arguing with your every thought about Finland, what does that mean?"

Sometimes when your skin is pressed against something for a while, it leaves a set of marks, a pattern. Sometimes the pattern is recognisable, especially if your skin has borne them before. You might recognise, for example, the shape of leaves of grass on your legs after you've been sitting on them.

In Finland, as a Black American woman ethnographer, I wasn't always pressed up against something new, but I was so firmly pressed against things that patterns were etched into my skin and I could explore them via my own body. Often a pattern was recognisable because it was generated by a familiar oppression, whether white supremacy, gender- or class-based oppressions, or all three at once. It was striking to me that one part of a pattern could be immediately familiar and yet diverge elsewhere.

For example, the way thin, white, abled Finnish ciswomen's bodies were represented in art and advertising as stand-ins for the nation, representing purity and whiteness, enticing would-be tourists through their beauty and nudity, was familiar. This fierce capitalising on some Finnish women's resemblance to contemporary white feminine beauty ideals was unsurprising, but the way this combined with state feminism to lend a complex and exceptional power to highly visible normative white women's bodies went beyond what I had experienced elsewhere. I was struck by the centrality of this exalted form of white womanhood for Finland's nationalism and global image, and by how it visually represented the idea of Finnish superiority in so many ways, from superior democracy to a superior relationship to nature. It evoked a fragile form of perfection in need of protection and preservation (a repeated implication was that the protection needed was from men 'of migrant background').

"Meaningful mimicry of Finnishness is not possible for a Black woman: this form of whiteness is out of reach. You don't fit, you can't fit, you stand out (like the nail that needs to be hammered down): your colour, your shape, your knowledge."

It was as if I was seeing the immense power of normative white womanhood for the first time. But where I was used to the (admittedly distant) possibility that I could join the ranks of the human, I found in Finland there was no real invitation. Finnishness managed to mix up and mix together nationality, language, genetics, a political economic logic, a relation to nature, and a specific form of whiteness in such a way that it can't properly be joined in with. Indeed, the suggestion was that I might damage Finland somehow, including by thinking the wrong thoughts. Meaningful mimicry of Finnishness is not possible for a Black woman: this form of whiteness is out of reach. You don't fit, you can't fit, you stand out (like the nail that needs to be hammered down): your colour, your shape, your knowledge. It makes it difficult to find the confidence to speak, even for someone who people hear as loud, angry, and overconfident.

The daily experience of unfamiliarity and all the ways I didn't fit and couldn't do the right things was itself familiar from other experiences as an ethnographer, where surely things being new and different and requiring one to learn to fit is the point. Yet, it was new to find an overwhelmingly cold, deeply disapproving, and humourless approach to my lack of fit and need to learn. It seemed there truly was only one correct way and it was out of reach. I could not learn fast enough the correct way to dress, comport, or even feed myself and my child, and I could not afford the immense monetary expense of this kind of fitting in, even if I had wanted to lose my clearly culturally inferior and déclassé ways (which I did not).

"It was as if I was seeing the immense power of normative white womanhood for the first time. But where I was used to the (admittedly distant) possibility that I could join the ranks of the human, I found in Finland there was no real invitation."

And yet the disapproval stayed with me uncomfortably, the marks on my skin more like welts than mere indentations. And this disapproval was communicated to me by white women, sometimes strangers, sometimes not, but never by Finnish men, whose habits of silence felt increasingly strange to me. White Finnish men's silent detachment (even in conjunction with power) indicated to me a very noticeably different conception of manhood that was complemented by the confident centrality of white Finnish women to all spaces I encountered. This left me dwelling on what it means when powerful people can so comfortably avoid engagement entirely and leave one to spin one's wheels alone. I was used to a form of domination where men discredit women, including Black women, quite overtly but here was something new.

Of course, I was also familiar with being pushed down by white women; I am after all in academia, where this is ubiquitous for women of colour. In Finland I was in contact with this pattern of behaviour so constantly that I cannot but have a more heightened awareness, a deeper knowledge of it. In particular, I have a keener sense of the way that class is entangled in all of this, playing an essential role in the policing of all aspects of life which middle class white women carry out on behalf of the nation, against working class white people and racialised people alike. It works so well you find yourself vainly searching within for the strength to push back or to thicken your skin so they can't press into you quite so far.

But who are you to resist a loudening consensus on your inferiority? It's not like you've not been told before.